I see a red door and I want it painted black

No colours anymore I want them to turn black

“The council’s position is not to make a judgement call on whether graffiti is art.”

Nahhhhhhh you don’t get out of the thorny issue of art and censorship as easily as that! Surely we need to see the Council itself as a creative agent (“the urge to destroy is also a creative urge”) – and Stoke Newington Church Street as an installation? A durational piece spanning several decades…

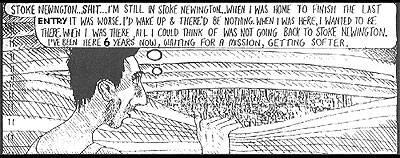

I’ve lived in Stoke Newington for about 12 years now (and was coming here long before that). I’d been aware of it for some time as it was the kind of place that cropped up with alarming regularity as part of the counter culture discourse of the eighties. The Vague cartoon above (circa the Televisionaries issue, 1987?) portrays the area as consisting of nothing but off licences and video shops.

It was better than that by the mid nineties – you had a load of cheap unpretentious curry places where you could bring your own beer, for example. After our daugher was born I would regularly wheel her (modestly sized) pushchair into Totem Records and have a rummage through their generally overpriced but still great racks while she gurgled away. And there were a bunch of good second hand book shops, and The Vortex jazz bar and caff, (which everyone raves about now but nobody ever seemed to be in there when the jazz was happening – it was rammed for the quieter weekend breakfast sessions). Somebody once told me that the Vortex used to be a Kangol hat factory, which I really hope is true.

I see the girls walk by dressed in their summer clothes

I have to turn my head until my darkness goes

Then we got Fresh and Wild, a huge and very poncey organic supermarket chain. Totem Records was replaced by a shop selling really expensive baby clothes. And suddenly there were loads of estate agents.

Slowly but surely there was less and less that I liked, and more and more bijou shops for “yummy mummies”. There was a bit of a ruck when The Vortex closed down, with a squatted occupation and anarcho “social centre”. I didn’t really bother all that much with it because I hadn’t felt a stake in the place or the street as a whole for some time by that point.

I generally find anarchist social centres a bit alienating these days. Around 2002 I popped down to the Radical Dairy after they got raided by the cops. Daughter tagged along in pushchair (we carried her in a sling when we marched against the war in Afghanistan in 2001. So yes, she is probably going to grow up to be a rabid Tory).

At the Dairy the usual subcultural suspects were sitting around (listening to some Tappa Zukie if I remember rightly). They were all nice enough, but I was pretty much pounced on when it was found that I lived nearby. Which I assumed meant that I was a rarity and the vegan caffs, library of Kropotkin pamphlets and weekly spanish lessons werent making great inroads to the local community. Once I’d been assigned the role of “local person” I fed them some lines questioning the police raiding the place rather than closing down the crack houses up on Stamford Hill, which I was pleased to see mentioned in the next issue of the Gazette. But I never felt the urge to go back there.

Don’t get me wrong, I have nothing against people taking over spaces and trying to do things with them. I would have loved for there to be something like that nearby when I was a teenager. I just think it is very difficult to break out of a subcultural scene and connect with “ordinary people” (whoever they are), and social centres for a while were heralded as doing that, when perhaps they weren’t.

I wanna see it painted, painted black

Black as night, black as coal

Church Street subsequently reached new levels of hysteria when Nandos bought the lease on The Vortex (after rumours of similar bete noires such as Starbucks and Tescos). There was a campaign website bemoaning “their desire to clog up the clean air of Clissold Park with the stench of battery farmed chicken grease and chip shortening” (Clissold Park is a good ten minute walk from the site, so that would have to be some powerful stench).

Aroma aside, the main objection to Nandos seemed to be the incursion of chain stores which would herald the end of Church Street’s unique parade of independent shops. Personally I don’t really want Church Street to be filled with the same chain shops you see everywhere, but if the alternative is increasingly expensive boutiques that I can’t buy anything from then I’ll take utility over independence every time. I didn’t see any protests against Fresh And Wild opening.

The simple fact is that the rents were going up as Church Street became an overspill for Islington’s Upper Street (in parallel with property prices increasing as young professionals who couldn’t afford to live in Islington moved to the area). So business owners either had to rely on high footfall and national back up (chains) or selling expensive niche stuff to rich people (boutiques).

Needless to say Nandos got their way in the end. And you will find me there occasionally, having a hungover Sunday lunch.

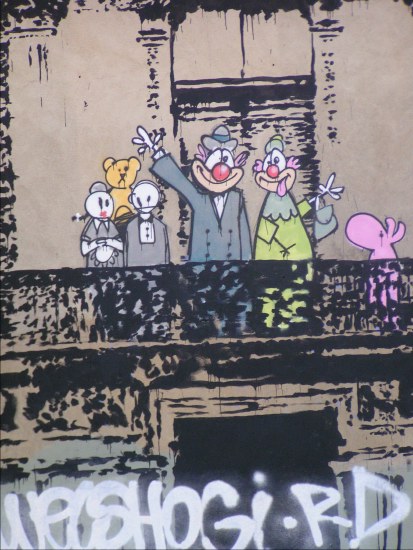

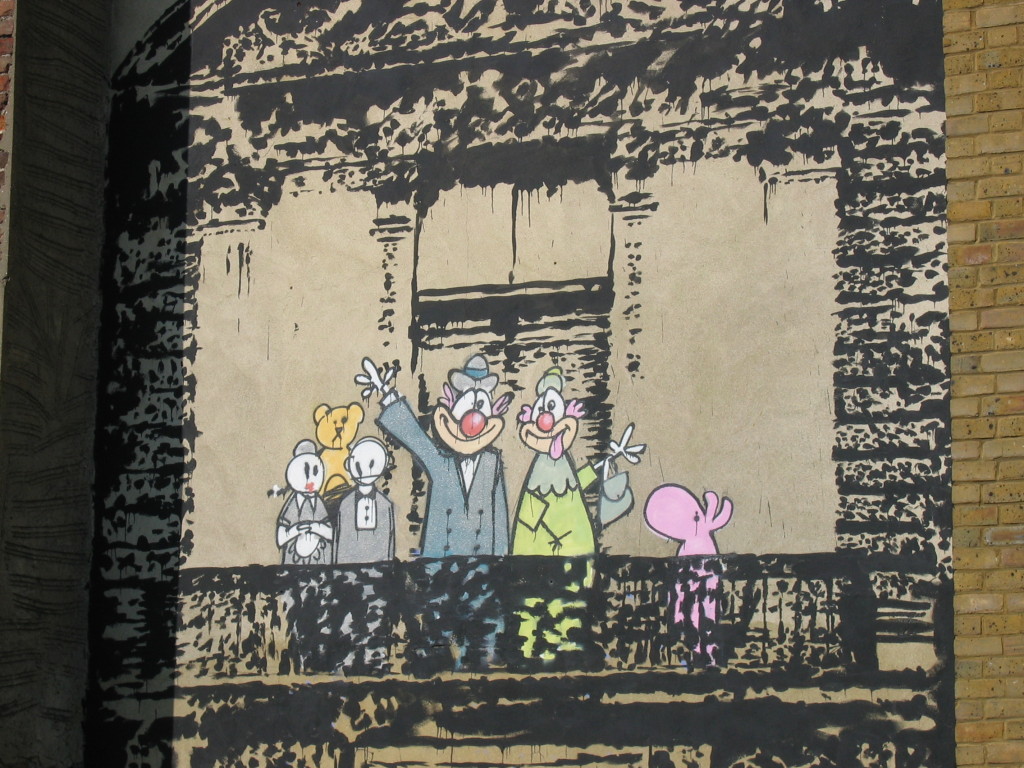

“How could anyone think it’s a good idea to paint the whole side of a building black?”

So this is a longwinded way of explaining the background to the Council painting over Banksy. Church Street has been changing rapidly ever since I first set foot there in the early 90s. Graffitti is by its very nature ephemeral – it also changes over time. You can see that the Banksy piece has been tagged over in silver in the “before” photo up top, for example. Encasing graffitti in perspex leads us down the road of commodification – removing precisely what is exciting about the medium: its illicit nature and impermanence.

Hackney Council’s latest work confirms all of this – the near eradication of the Banksy is a satisfying response to my feelings about Church Street – what has already been lost, and what is to come.

I wanna see the sun blotted out from the sky

I wanna see it painted, painted, painted, painted black

I just think it is very difficult to break out of a subcultural scene and connect with “ordinary people” (whoever they are), and social centres for a while were heralded as doing that, when perhaps they weren’t.

This was always described as “outreach” around here. I found it a really disingenuous and condescending concept, especially when it was expressed in terms of ‘x’ group (Palestinians, for example, who could get a few thousand to march on Parliament Hill) “needing” “help” from local anarchists (who could barely muster 30; 100 if Montreal showed up). “If only we could teach them about Bakunin and Black Blocs, then the government would have to take notice (oh and it would legitimise us too).” They didn’t think much of reggae either, come to think of it. Nor spicy food.

A portion of the longer article ‘Local Tradition, Local Trajectories and Us: 56a Infoshop, Black Frog and more in South London’ that talks about what is referred to in Jon’s article. I think it makes some sensible points about squats and social centres and the notion of ‘ordinary’ people.

”

2) A few individuals in the Black Frog and at 56a Infoshop had some criticisms of some very particular aspects of the more recent London social centre model. These aspects are well represented in the article ‘The Spring of Social Centres’ (in Occupied London, Issue 1, 2007) although we bear in mind that it was written by one very active participant in those centres from 2002 onwards.

The article, although it gives a nod to ‘a long history of occupied political spaces’, tends to stereotype pre-2002 centres as ‘squatter’ spaces characterised by subcultural disrepair and dogma (‘pissed up punks drinking Special Brew’, ‘dreadlocked brethren’). There are many examples of places that were like this but maybe as many places consciously tried to not be like this: Mutual Aid Centre in Liverpool, A.C.E in Edinburgh, Use Yr Loaf in South London to name a few only. Maybe it’s useful to say that just as pissed punks and trustafarians may be alienating to others, the anarchist militant, the anti-capitalist activist, the social centre type etc can be just as off-putting. We had fun at one recent social centre when we got told off for putting leaflets down on the leaflet table. ‘Sorry’, we mumbled. ‘Can we leave some flyers here?’, we asked. ‘What is it?’, he said with a tone. ‘It’s about 56a Infoshop, a social centre’, we said. ‘Never heard of it!’, he grunted. What can you do?

When the anarchist collective The Wombles began to initiate the recent London spaces, it was consciously modeled on the Italian social centre experience. We have always felt that although that Euro inspiration is often good (local political work around work, racism, gentrification etc but also the willingness to debate theory useful for activity), the politics of many Italian centres remain tied to an outdated Leftist project that often seeks alliances with reformist unions or local municipal power and is comfortable with social centre movement ‘leaders’ and hierarchies.

It seems important then that instead of dismissing earlier U.K centres for faults, it would be better to recognize commonalities between them and the European social centre model and work with that. Those old enough to have been active in and around the 80’s and 90’s centres could tell of very useful, creative and strong work in and around dole struggles, Poll Tax, Miner’s Strike, anti-fascism, elections, housing and squatting struggles etc. It was then that these centres seemed to come into their own (albeit often only temporarily and that’s a lesson worth living through for some kind of perspective of how political movement seems to be). It’s also good to remember that many of us were regular visitors to in/famous centres in Holland, Germany, Spain and Italy and were just as inspired then as The Wombles would later be. It doesn’t seem to us like the ‘new’ social centre model is so much different from the old squatted centre one. The problems we focus on are the same: work, not-working, housing, policing, racism, war etc.

What seems a bit skewed to us is the imagined effects of these newer centres on what’s described as ‘political activation’: ‘Thousands of people have passed through’ these new centres. Acting as ‘political and cultural hubs’ and as a ‘first port of call’ for ‘ordinary people’, magically ‘interaction with anarchists becomes normalized and barriers fall’. Later in the article there is some attempt to ‘quantify the scope of this embryonic movement’ with some guestimation about numbers passing through the post-2005 nationwide social centres. Although a figure of 4000 – 6000 people attending U.K centres over a period of time is great, there is no real sense of what this means for the people running centres, the people that come to the spaces or wider political resistance itself. In London, a vast city space with a whole different range of local and territorial communities that rarely overlap, it’s really difficult these days to see what goes on, what sustains and grows and what is a waste of time. (Of course we aren’t saying that a networked mass of social centers in loads of parts of London wouldn’t be great if they could bring into effect something dynamic, angry and useful and with this in mind we were often inspired by meetings and events at the recent London centres).

Back and Forth, Round and Round

At 56a (and this was true for the Black Frog) we see again and again different people come by, be excited but never return. At the same time we have a regular small coterie of annoying people who are draining. Happily we also have a small steady band of regulars who came by at least once every week. With this in mind we aren’t interested in numbers, in ‘quantity’. We are interested in working together, at all stages of our common experience and knowledge, be that 100 people or only 20, or only 5 people. In the end, just before the eviction of the Black Frog, we felt that we had moved to a new stage in the centre’s existence, that of being a growing local hang-out for self-defined rebels, disgruntled local people and interested people who had not come across anything like this before. This state of affairs did not come about through ‘ordinary people’ meeting some anarchists who happened to have all the cool and great ideas. It just flowed from spending time around each other and seeing what we had in common. Listening, learning, laughing, being pissed off about things together etc. It was shame we got kicked out at that point when it seemed like there was a possibility to open out the centre even further and to begin to initiate other projects outside of the space (The better part of ‘The Spring of Social Centres’ article talks about this seemingly inevitable process).

”

Whole article here:

http://socialcentrestories.wordpress.com/2008/04/24/local-tradition-local-trajectories-and-us-56a-infoshop-black-frog-and-more-in-south-london/

‘The Spring of Social Centres’ article referred to in the text:

http://www.occupiedlondon.org/the-spring-of-social-centres/

I went up to Stoke Newington in 1980 to look at some bedsits as I needed a place to live, but in the end felt a bedsit in New Malden (Sarf London mate) was more attractive… But 5 years later I moved to Manor Road (via Kennington) and already you could see the gentrification of Church Street beginning… It just seems to have gone on and on since then…

I guess the level of integration with the locality at different social centres/squats varies, in the eighties and nineties most of the people you saw in Freedom Bookshop (for example) were from outside London. That old geezer Donald always used to ask people if they’d come from far, he asked me this one time in the nineties when I was living less that 15 minutes walk away and I said: “Yes, I’ve come all the way from Bethnal Green, I live on the Avebury Estate at the top of Brick Lane and I had to walk all the way down Brick Lane to get here!” That really pissed him off, because of course he was more used to people saying, yes I’ve come from Germany or Italy….

Totally agree about Banksky … witty, funny cartoons (hardly great art, but good satire) that can only succeed if they remain graffiti, with the risk of imminent destruction … mystified why people want to turn such things into leaden gallery-pieces that needed to be protected.

I’ve seen Stoke Newington change too, over a similar period of time. The bottom line is that London changes; you have to accept it. In the mid 19th century, it was all bankers and the well-to-do, then it changed to working-class and immigrants in 20th. Now the bankers are returning …!

Still quite like it round here, mind you.

Thanks Lee! – Yes I’ve come to *accept* it, liking it is another story though 🙂

This is interesting in regard to the recent “restorations” they’ve done out here to the Los Angeles river banks, historically a free-for-all zone for graffiti and tagging. It’s practically a no mans land (as in, not a gentrified neighborhood… this stretch of river runs between the train tracks and the freeway), but for some reason the city council decided to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars (taken directly from the stimulus bill money meant to jump start the economy and the community) to cover up this “blight”… including some very famous works that had been there for decades. More info:

http://saberone.com/blog/2009/09/09/whitewashing-the-la-river-2/

http://puregraffiti.com/art/2009/09/saber-la-river-graffiti-buffed/

http://lacreekfreak.wordpress.com/2009/12/28/graffiti-the-los-angeles-river-and-the-federal-stimulus/

“Businessman to paint over Banksy artwork ‘because he doesn’t like art'”

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/artsales/7266588/Businessman-to-paint-over-Banksy-artwork-because-he-doesnt-like-art.html

wow that’s quite mad all round!

Pingback: UNCARVED.ORG BLOG » BLOG ARCHIVE » ELECTION SELECTION