BREAKING AND ENTRY

Listen

to the beat thieves says NORMAN COOK of The Housemartins as he

explains what Break Beats are and how rap stole out from beneath

their sonic clatter.

Most

people with more than

a passing interest in music will know something about hip-hop or rap,

but ask even a music journalist about Break Beats and most of them

won't have a clue what you’re on about. Considering these beats are

a DJ technique that

has been

going on for 15 years

and were

largely responsible for the birth of

rap, that’s a

real shame. So read on.

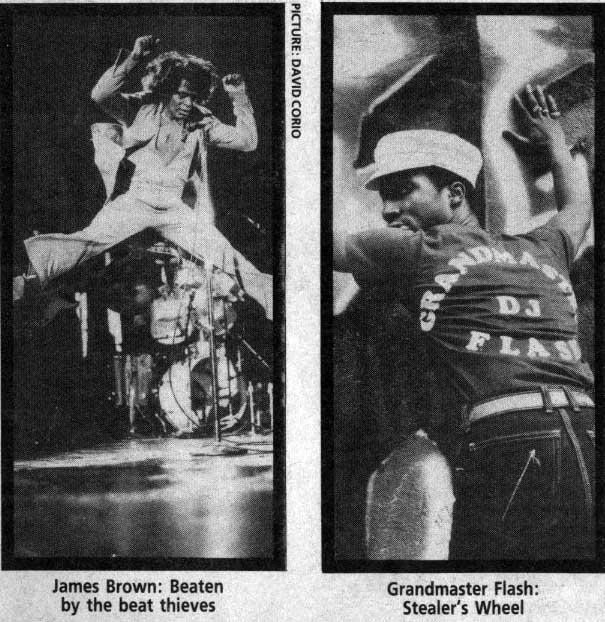

The story starts with New York block parties in the early ‘70s. DJs – including Kool DJ Herc and Grandmaster Flash (probably he best known) — would plug homemade soundsystems into neighbourhood centres, parks and basketball courts in black areas and launch dance marathons that are now legendary.

The music they played however was not hip-hop or rap; such records didn’t exist. What they did play was soul, early funk, Latin and jazz. Operating twin decks, they began to develop new styles of mixing the records which won respect and applause from the crowds. Scratching, now well known and used throughout pop, was one of these techniques, but more important at that time was the process of cutting break beats…

Always keen to please, DJs began to notice that the crowd, and especially the dancers, responded best to the drum breaks in some funk and Latin records.

For the dancers, the percussion breaks seemed to be the highlight of these records, yet some were only four bars long. Why not extend these breaks by mixing two copies of the same record on the twin decks? While one deck was playing, the DJ could cue up the start of the same break on the other deck and, using the faders, cut it in on the beat. By this method a DJ could elongate a ten-second drum break to two minutes and take the dancers, who developed wilder and more energetic routines to the percussion, to higher levels of excitement. These dancers became known as break dancers and the rest of their story is history.

DJs became respected and admired for their use of breaks and their skill on the turntables. Inevitably intense rivalry grew between them. They could attract the biggest audience by playing breaks no-one else had, and so began searching their record collections for rarer and better breaks. Not only funk and soul records were used; anything with a good drum beat could be plundered and sometimes the DJ would play only the break and ignore the rest of the record! Tracks like ‘Honky Tonk Woman’ by The Rolling Stones, ‘Mary Mary’ by The Monkees and ‘Johnny The Fox’ by Thin Lizzy were used alongside more predictable funk tracks, European electronic music like Kraftwerk, and pop like Visage’s ‘Pleasure Boys’. The competition became so intense that DJs would scratch the title, or soak the label from rarer records so as to conceal their identities.

And it was not only what was played that won audiences and reputation, it was how it was played. For the better DJs speed and accuracy came with practice, until they could repeat phrases at incredible speed. Consoles with cross faders required only one hand to cut from one deck to another, leaving the other free to wind the turntables back at great speed.

People

like Grandmaster Flash and Grandmixer D.ST, could cut ‘Good Times’

by Chic, perhaps the

most

famous break, so quickly that they were repeating the phrase ’Good

Times’ back to back, and then repeating just ‘good, good, good’,

their hands flying from deck to deck faster than the eye could

follow.

People

like Grandmaster Flash and Grandmixer D.ST, could cut ‘Good Times’

by Chic, perhaps the

most

famous break, so quickly that they were repeating the phrase ’Good

Times’ back to back, and then repeating just ‘good, good, good’,

their hands flying from deck to deck faster than the eye could

follow.

Nor is it a coincidence that the first big Rap

hit,

‘Rapper’s Delight’ by the Sugarhill Gang, used the Chic rhythm

track. DJs, ever competitive, had taken to using masters of ceremony

with microphones to encourage the audience and praise the

disc-spinner. They would do this in time to the breakbeats, chatting

and bragging in rhyme, following a very old tradition in black music,

one dating back to the blues of the ‘30s.

In the early days there were no disco records with instrumental B-sides or drum machines to use as beats so these MCs would rely (as many still do) on a DJ with two copies of a break like ‘Good Times’, ‘Funky Penguin’ (by Rufus Thomas) or ‘Heartbeat’ (Tania Mason) to provide their beat. These ‘rappers’ developed their routines to the point where the cheerleader became artist, and rap crews like the Furious Five, Ultimate Three and Cold Crush Brothers grew more famous than their sponsoring DJ. Again, the rest of their story is well chronicled...

Perhaps

the reason

why Rappers and Break Dancers have found more fame than break beat

DJs is that copyright laws prohibit making a record out of somebody

else’s, Therefore, very few break beat records bar ‘Adventures On

The Wheels Of Steel’ by Grandmaster Flash, and ‘Breakdance —

Electric

Boogie’ by West St Mob (the latter made entirely out of perhaps the

greatest break beat, ‘Apachie’ by The Incredible Bongo Band) —

were ever

released. Even Grandmaster Flash, the greatest DJ of them all,

featured only on one record, taking a drum-machine back-seat for hits

like ‘The Message’ and ‘It’s Nasty’.

The copyright

laws reared their ugly heads again in the matter of the availability

of break beats to DJs themselves. Many of the rarer beats became so

sought after that people began to bootleg them. Paul Winlen started

putting out his ‘Super Disco Break’ LPs (poor quality

reproductions of rare breaks) in the late ‘70s. This market has

grown steadily; ‘Octopus Breaks’, ‘Hardcore Breaks’ And

‘Fusion Beats’ bootlegs have all appeared and Streetbeat Records’

‘Ultimate Breaks And

Beats’ series, available in this country, now runs to 14 volumes.

And Morgan Khan has announced the forthcoming release of a legal

break

beat LP.

Many artists, however, have recently beaten the

copyright laws by using only snatches of beats over the top of drum

machines. Hence Sweet Tee’s ‘It’s My Beat’ features James

Brown’s ‘Funky Drummer’, while Run DMC have cut Bob James’

‘Mardi Gras’ and had their huge hit with a version of Aerosmith’s

‘Walk This Way’, a classic break beat.

Over

the last

four years, the popularity of break beats has grown considerably in

this country. The proliferation of live, and radio, mixed tapes, and

of break beat boots, is proof that (try to get hold of ‘Feelin’

James’ on TD Records or to hear Double Dee and Steinski’s ‘Lesson

3’ — a

brilliant collage based around Herman Kelly’s ‘Dance To The

Drummer’s Beat’ and a great introduction to break beats). And

while the limited appeal of drum breaks as a pop form will probably

ultimately restrict them to cult status, the mixing throwdowns

between local DJs like Jazzy Jeff, DJ Cheese and Afrika lslaam will

continue to pack out clubs in London and elsewhere.