FAIRLIGHT ROBBERY

Does sampling mean the

end of pop civilization as we know it? LOUISE GRAY steals the

thoughts of the sonic smash-and-grabbers.

Fil Chill (The Three Wise

Men): “Computers are the sound of the future. Computers will

change the sound of the music industry. Very soon, everybody will be

able to make records.”

We

are here to mourn the death of the song and the death of that fleshly

trace the song inevitably bears —

the figure

of the singer/songwriter, closeted alone in his room, the inventor of

all meaning and the Centre of all angst I’m talking to you, Mr

Morrissey, the sensitive and solitary artist, to you, BonoVox, rock

prophet, and to you, Mr Springsteen, the last prole in town!

For

we are witnessing the birth of a new generation, the pop children of

the new technology. They reject your Luddite ways, deal not in songs

but soundscapes, don’t create, but assemble. Computer-generated

music is poised to challenge your every practice; I don’t mean

synthesiser bands (who both looked and sounded like automatons), I

mean sampler-musicians/creators/producers who seize from the library

of recorded sounds, not history, but moments.

Punk

made to us the election promise that ‘anyone can do it’, but

lacked the technology to back the rhetoric. It was a new idea in old

clothes, still dependent on drums and wires, even Sid Vicious bad to

play bass. Punk was the anticipation

of

sampling.

This new, usable technology will erode away the

privileged position of the artist, of the musician, who, too often,

is revered not for what he can do, but for what others can’t. An

increasing familiarity with machines has shed technology of its

mystique. Sampling, by turning the studio into a compositional tool,

gives talent an infinity of new voices. Future shock, or what?

Think of the sampler as a recorder attached to a keyboard; substitute

floppy computer disks for cassette tape, and you’ll get an idea of

its possibilities. Samplers invariably come in the form of keyboards,

for the new technology must ape the forms of the old, with an input

socket for your sound source, be it a ‘live’ sound or a

previously recorded one. The machines differ in the length of the

sample they can, at peak recording, take. The cheapest Casio SK-1’s

sample limit is 1.4 seconds; the mighty Fairlight Series 3 has a

limit that stretches into minutes.

Take that sound

‘naturally’, or treat it, bend it, reverse it, stretch it. Sample

two seconds of The Smiths and skank them up! Sample a scale from Nico

and make her play ‘Happy Talk’! The history of recorded sound is

at your fingertips. A

synthesiser

uses sounds that are located within its circuits, an electric guitar

makes noise via vibrations, but a sampler ‘takes’.

When

the Musicians Union and BPI between them came up with those slogans

on a thousand guitar cases —

“Home

taping is killing music” and “Keep music live” —they hadn’t

considered the sampler. But the true significance of this

development is not so much in what it does, but what it

implies.

When

it’s cheaper to sample than buy a guitar (the SK-1, bought by

buskers, parents and the curious as the ultimate coffee table toy,

starts at £69; the Fairlight 3 at £60,000, but there’s a myriad

of points between the two) why sweat? Why try to play like Hendrix

when you can rip him off?

Like

it or not the silicon implants of computer technology have co-existed

peacefully with the strings and wires of the Pop Group for a handful

of years. Through a laborious diligence, you would learn your guitar

chords, single out middle C, kick your bass drum, drag the lot to a

recording studio, and let the engineer get on with it. He may use

banks of strange machines that look like the Enterprise

flightdeck,

but that’s no problem. After all, a technician is not a musician.

Anyone can see the clear division of labour. Look towards the horizon

more closely; those rosy days are all but over.

A

new technology has entered pop as previous technologies have never

done before. Ten years ago, no ordinary-incomed band could afford a

synthesiser. Ten years ago, using a synthesiser was sufficiently

complicated to ensure that the end product was either mundane

pomp-rock of the Magazine variety or the minimalist one-finger chord

oceans of Numan and early Human League. It was only those bands with

technological backgrounds—the Kraftwerk engineers being the prime

example —

that seemed

truly at ease with their machines.

You could say that

microchips have democratised that access to technology

(and the music itself), and

opened that road previously blocked by income or education. Of these

pieces of hardware —

drum

machines, synthesisers, sequencers —

nothing is

more important than the sampler. Sampling has brought technology down

from the studio and onto the street.

Sampler-musician John

Oswald is an interested participant in the arena where machines meet

music. Introducing his essay, plunderphonia,

he

writes:

‘A

digital sampler is, in its most common form, a

tape

recorder which looks and acts like an electronic

organ. Samplers have become prominent in modern music making and are

receiving the sort of publicity in the popular press that

synthesisers did two decades ago. Musicians once again fear their

impending obsolescence.”

“A sampler, in essence a

recording

transforming instrument, is simultaneously a documenting device and a

creative device, in effect reducing a distinction manifested

by copyright.”

(Recommended

Records, Volume 2, Number 1, Spring 1987)

Or, in the words of

Mixmaster Morris, the sampler behind both The Rhythm Method and ‘The

Mongolian Hip-Hop Show’, of London’s pirate radio station,

Network 21, fame: “Sampling doesn’t theoretically offer you

anything that you can’t do with a razor blade and a spool of tape,

it’s just that you’re less likely to cut your fingers, it takes a

lot less time and the process is reversible.”

EVERYBODY’S

DOING IT D-D-D-DOING IT

All but the most tenaciously manual bands do it. The chart

residents (though coy in admitting it) do it too.

The engineers

behind Mel and Kim sample; Mirage sample Mel and Kim, Kraftwerk,

Farley ‘Jackmaster’ Funk; hip-hop—the most upfront form of

music in admitting its sources —

relies

on

them. The indie charts, clinging onto guitars

and (real) drums for grim death, are Luddite by comparison. The more

the charts rely on seamless studio sounds, the more acoustic the

indies become, in some vain assertion of rock ‘n’ roll

authenticity. The very people who welcomed punk’s gatecrashing of

the music industry now fear the death of pop. If there’s such a

thing as a conventional pop format it’s one based on standard

instruments. You don’t have to play them as nature intended. Pete

Townsend still got sounds out of his guitar when he smashed it, or

Little Richard tones from his piano when he walked on it.

In

the theatre of pop, the instruments were there to be seen, the means

of sound production had to be visible.

Thus,

we get the spectacle of Paul HardcastIe dancing across our Top

Of The Pops screens,

a keyboard dangling from his neck. If he hadn’t

been miming

it was

an unlikely way to ‘play’, but at least there was no need to

question authorship of the music.

Whether or not sampling

de-skills the musician isn’t the question. It allows non-musicians

the possibility of performance by all

sounds

musical. Peckham-based rappers The Three Wise Men, are a case in

point. Contained in their ‘Urban Hell’ collage are sampled glass,

motorbikes, traffic, the sounds of the inner city.

Jemski

“Metal is an urban sound. It reflects our environment. We get our

sounds from everywhere like that revving up sound. We took two good

mikes onto the Harrow Road and chanced upon this motorbike that was

starting up, we just recorded it

into a

digital recorder”.

In Chicago, House producer and Bang

Orchestra maestro Vince Lawrence is likewise sampling the sounds of

the city, his city...

“Trax, the studio I work in is in a

gay community. Round the back car park, we came across two guys sort

of going at it. Their sounds were so natural, me and a buddy grabbed

a couple of mikes and recorded it, then pulled samples off it.”

It’s

the artist-in-a-garret scenario updated. No longer will generations

need to closet themselves with Bert Weedon guitar- tutors; their

act of

rebellion will be sampling.

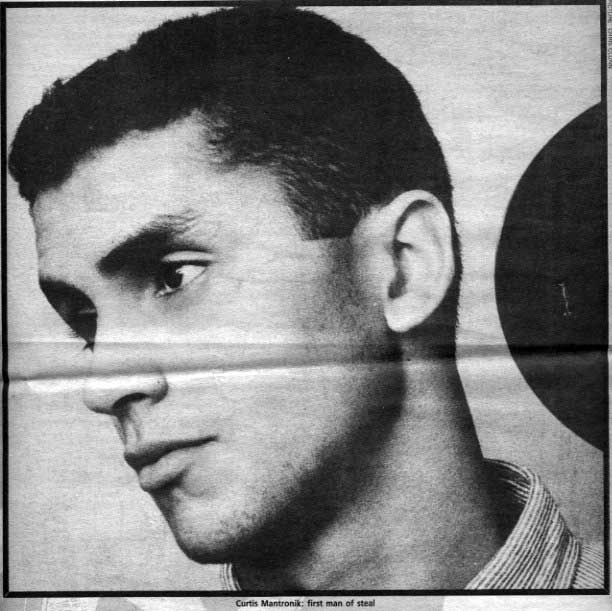

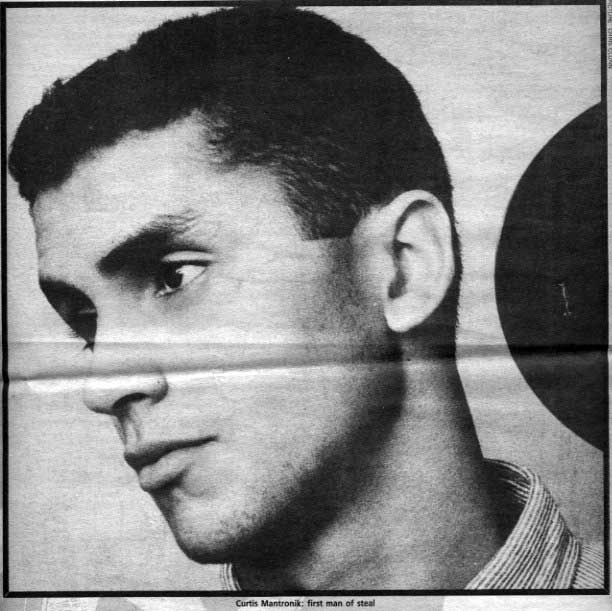

Curtis Mantronik, creator of the

first completely sampled album, ‘Music Madness’, started out in

the bedroom with a drum machine; now he lives in Manhattan surrounded

by three samplers and a pile of secret ingredients. Taking the ease

of sampling to its logical conclusion, allying it with other equally

cheap, equally accessible technology —

portastudios,

televisions used as computer monitors, and a bit of software —

the

sampling revolution’s set to take on the quantifiable profits of

studios; the cost of studio-time has always been the deciding factor

to anyone attempting to break into records.

Jemski: “When

for two grand you can have a computer (The Wise Men use Atari with a

Steinberg sequencing software package) that can do the best that a 24

or 48-track studio can do in your home —

£2,000

would normally pay for a couple of days time in one of those places—

it’s going to make the studios redundant”.

“And,”

adds drummer, Fil Chill, “kill the record companies”.

“There’s

a lot of people who want to make music,” Jemski continues “but

they couldn’t generate the funds to do it. With this

technology, everyone will be able to do it and just pay for the

master cut. At the end of the day, it’s going to be the people

who’re good that sell the records, and the people who ain’t,

won’t. At least it’ll

be

the public who decides. A situation of complete freshness is

happening." Reading between the lines of Jemski’s rhetoric, the

corollary of the demise of studio tyranny is the destruction of the

constraints that control musical talent.

Contained in the

accessibility of a sampler is the creation of new talents free of the

notions of musical technique. As the roles of producer and musician

merge into one, no longer will your ‘musicianship’ be defined by

your instrumental ability, only your imagination. That’s where the

buck stops.

For every ten people who come to the sampler with

ideas, there are a thousand without them.

Mantronik: “These

hip hop kids go into the studio because there’re certain people

they’ve followed, but they don’t fully understand how that

process works. If you hear most of the hip-hop records, the samples

that they do are very poor, poor quality, just because they don’t know know

what’s going on. It’s real easy to do a sample, real easy to put

something in a machine and sample it, but to make a good sample, make

it work, it takes something else.”

House music is the ultimate producer dance

language. The musicians who made the original snatches of sound are

faceless and uncredited; the producer-cum-DJ is the vital element in

the mix. Who plays piano for JM Silk or Jackmaster Funk? Who cares?

The authorship of the record lies not in its origins (in the playing)

but in its sonic splicing. Vince Lawrence, originator of ‘Sample

That!’, moved into House from a producer background. He’s not

threatened by the Wise Men’s apocalyptic view of the studio culture— “Burn

them down, burn them down! Burn the f*ckers

to the

ground!”

“I

say that if a kid with $500 can go and make a record, contribute his

art to the world, that’s fine,” says Lawrence. “As a musician,

he’ll be more talented, he’s going to get more edge. Kids banging

in the garage are going to be kids. Professional bands are going to

be professional bands.”

How do you define yourself, then,

Vince? Are you a producer or a musician?

“Me? I’m an

artist.”

THE

RIGHT TO COPY

THE

RIGHT TO COPY

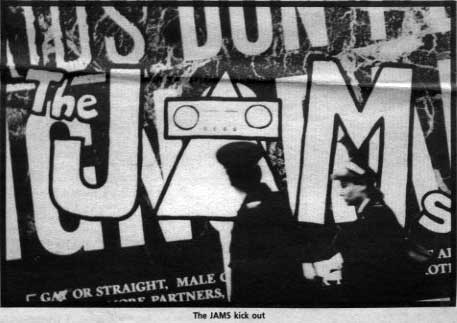

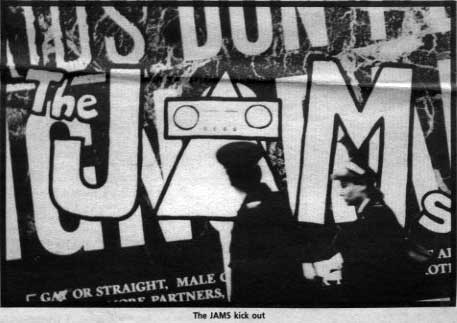

The Justified Ancients Of Mu Mu (sampling duo King Boy D and

Rockman Rock) have come from production backgrounds and started

kicking the notion of copyright where it hurts most —

the wallet.

Their ‘All You Need Is Love’ 45, and debut LP, ‘1987 —

What The

F**k’s Going On?’, steal relentlessly —

the single,

notably from Sam Fox’s ‘Touch Me’.

King Boy D: “We

were aware of copyright, but it was only once we’d done ‘All You

Need Is Love’ and finished our album, and been told that we

couldn’t do this sort of thing, that we come out with KLF —

the

Kopyright Liberation Front. It’s like it’s 1955, and you’ve got

yourself an electric guitar, and then somebody from the Acoustic

Guitar Society comes around and says ‘I’m sorry, you can’t do

that; it’s against the law to use electricity in instruments’.

And that’s what it feels like; we’ve got these samplers, how are

we meant to use them?"

“We thought everyone was going to sue

us, but it hasn’t happened. A solicitor told us that if

we got

caught it’d cost us a minimum of £10,000— and that’s just

withdrawing the record not fighting it

in court.

All my neat lines of how we weren’t taking, but creating something

new, just didn’t

wash. In a

couple of sentences this solicitor just ripped us apart. However,

Jive Records —

Samantha’s

label —

have

approached us for a record deal”

Rockman

Rock: “They should be sueing the bollocks off us.”

Wait

until Abba hear the album; with ‘Dancing Queen’ used in its

entirety as a backing track on one song, they’ll be sending the

longboats over.

So, everything may be found, but it’s not

free. The courtrooms are set to reverberate with the echoes of the

George Harrison ‘My Sweet Lord’/Chiffons ‘She’s So Fine’

lawsuit, sample-style. No legal precedent exists yet as to who owns

the sonic airwaves; the arbitrary figures of seven seconds or four

bars have been mentioned, but nothing’s definite. The Beastie Boys

sued British Airways for quoting a tune, then settled out of court

over their Led Zep habit. It may be fashionable to take a Cameo drum

beat or a James Brown riff, but if anyone’s tempting fate in

Britain, it’s the Justified Ancients Of

Mu-Mu.

‘All You Need Is Love’ not only quotes but references chunks of

The Fab Four, MC5, Abba and our Sam. Is this a naughty debunking of

copyright or musical madness?

King

Boy D “No, the naughtiness came about afterwards. We made that

record out of what excited us, out of what we had lying around. When

we came to getting it released, nobody would distribute it for us,

not the Cartel, nobody. They didn’t want to go to prison, be sued,

go to court. It wasn’t like one of your import hip-hop records with

a bit of James Brown on —

nobody’s

worried about that. We were a British group wanting it distributed by

British distributors, so it was more upfront”

Theft is a

form of flattery, even though the Master of the Drum Rolls may decide

differently, but is there a difference between quotations and

plagiarism? As befits a

classicist,

burdened with the concerns of authorship, Roger Bolton (main man of

Syco Systems, Fairlight’s UK distributor) tells the musicians that

he samples from what he’s doing, and pays double the going rate.

And will he credit them?

“I’m negotiating with Fairlight

a slightly new contract that we will give to every new user; it says

that if they do any sampling, they make sure they get the name of the

musician and credit them every time they use the sound. It gives

the musicians more publicity, and hopefully, more work.” That’s a

predictable, traditionalist response. Isn’t sampling a freedom from

all that?

“The whole idea of sampling is to generate new

sounds from combining old ones and manipulating them. God, I’ve

stolen snare drum sounds before. But the point is, that I won’t

just play them back, I’ll put my fingerprint on it somehow.”

WHAT

FINAL FRONTIERS?

Sample

that! The entire history of recorded sound is available for

restructuring, retransmission, for causing a revolt in the museum.

Music has always relied for its justification on a theory of roots;

it has always referred back to the past. Not for nothing does the

question, rephrased and repeated, ‘Where’re you coming from?’

exist.

The possibility of sampling is the removal of all

historical reference points, the production of an ahistorical

amnesia. And an infinity of new musical meanings. By severing some

sound from its origins for your own sampling purposes, you’re not

merely vivifying history, you’re —

through collage, quotation, pastiche, bricollage —

remotivating

fragments with these new meanings. A

sampled

sound becomes fraught with meaning.

King Boy D: “There’s not much of ‘Touch Me’ on ‘All You Need Is Love’, but it’s putting Sam Fox in a context. Whereas she tries to portray herself as good clean fun, part of the British way of life – happy Samantha! – we’re putting her in another context, exposing her double standards. We’ve inserted “touch me” between “shag, shag, shag” and lots of (male) deep breathing...If I was Samantha’s dad, I wouldn’t be too happy.”

Rockman Rock: “The record was loosely about AIDS; there’s no intellectual thought behind it, just a series of images.”

Stripped of its roots, all the music in the world has already been written. There’s nothing left to discover, only things to reinvent; there’s no pure, raw music, only the prepared.

Mixmaster Morris: “I often sample off records but distort it in such a way that I can never find the sample again. There’s a lot more to sampling than just name-dropping. It’s a perfectly valid technique, but I like to go a lot further and make something completely new out of samples. I use the cooking analogy: you can be a great cook without inventing new ingredients, you just mix the old ones in a new way. In the same way with music; by crossing unusual things you’ve created something original.”

Sampling means cannibalism, chewing your chosen musical morsels just as much as you want, swallowing them whole, throwing up and rearranging. Pop eats itself.

THE

RIGHT TO COPY

THE

RIGHT TO COPY